THE RISE AND FALL OF THE TRIUMPH HERALD

08 March 2023

On 22nd April 1959, the Albert Hall paid host to a new car from Canley. An audience of the motoring press and dealers could enjoy a musical gala with rock & roll dance numbers and – the piece de resistance - a team of engineers building a Herald Coupe on stage in just four minutes. The Motor though described the latest Triumph as ‘a most promising newcomer’ while The Daily Telegraph raved about the ‘road-holding characteristics only found normally in high-priced sports and racing cars.’

Ten years earlier, the idea of a small mass-market Triumph capturing the zeitgeist would have been unthinkable to many drivers. Standard Motors acquired the famous Coventry firm in 1945 and at the end of the decade, their output was the Renown, a stately-looking saloon aimed at the ‘touring car’ market for tweed wearers. In 1950 it was joined by the 1,247cc Mayflower, which was not overly successful.

However, when the TR2 entered production in 1953, it transformed the image of Triumph to the extent that the Standard Eight and Ten were renamed for certain export markets. Their Herald replacement was to be a more upmarket machine; £702 2s 6d for the Saloon and £730 14s 2d for the Coupe was more expensive than its Austin, Ford or Morris rivals. It, therefore, made sense to use the Triumph name for the car you could ‘park with pride!’

From a customer’s perspective, the Herald boasted the fashionable ‘Italian Look’, courtesy of Giovanni Michelotti, and fittings including a heater, windscreen washers, a trip recorder, a reserve tap for the petrol tank and even adjustable steering. In addition, the Coupe featured a water temperature gauge and a lockable glovebox. The brochure claimed, ‘No words can capture the magic of the Triumph Herald’ and asked, ‘Do Men Drive Better Than Women’. Predictably, the answer was ‘Not in the Triumph Herald!’

Meanwhile, the technically minded driver would be familiar with the 948cc motor from the Standard 10, but the rack & pinion steering was a departure from the S-T norm. Furthermore, all -independent suspension was a ‘first’ for a mass-produced British car – the Slough-built Citroëns were assembled – and the Herald also featured a sperate chassis. Plus, there was that remarkable engine bay accessibility, and a 25-foot turning circle, even if the Saloon’s 71 mph top speed was not exactly ideal for the new ‘Motorway Age’.

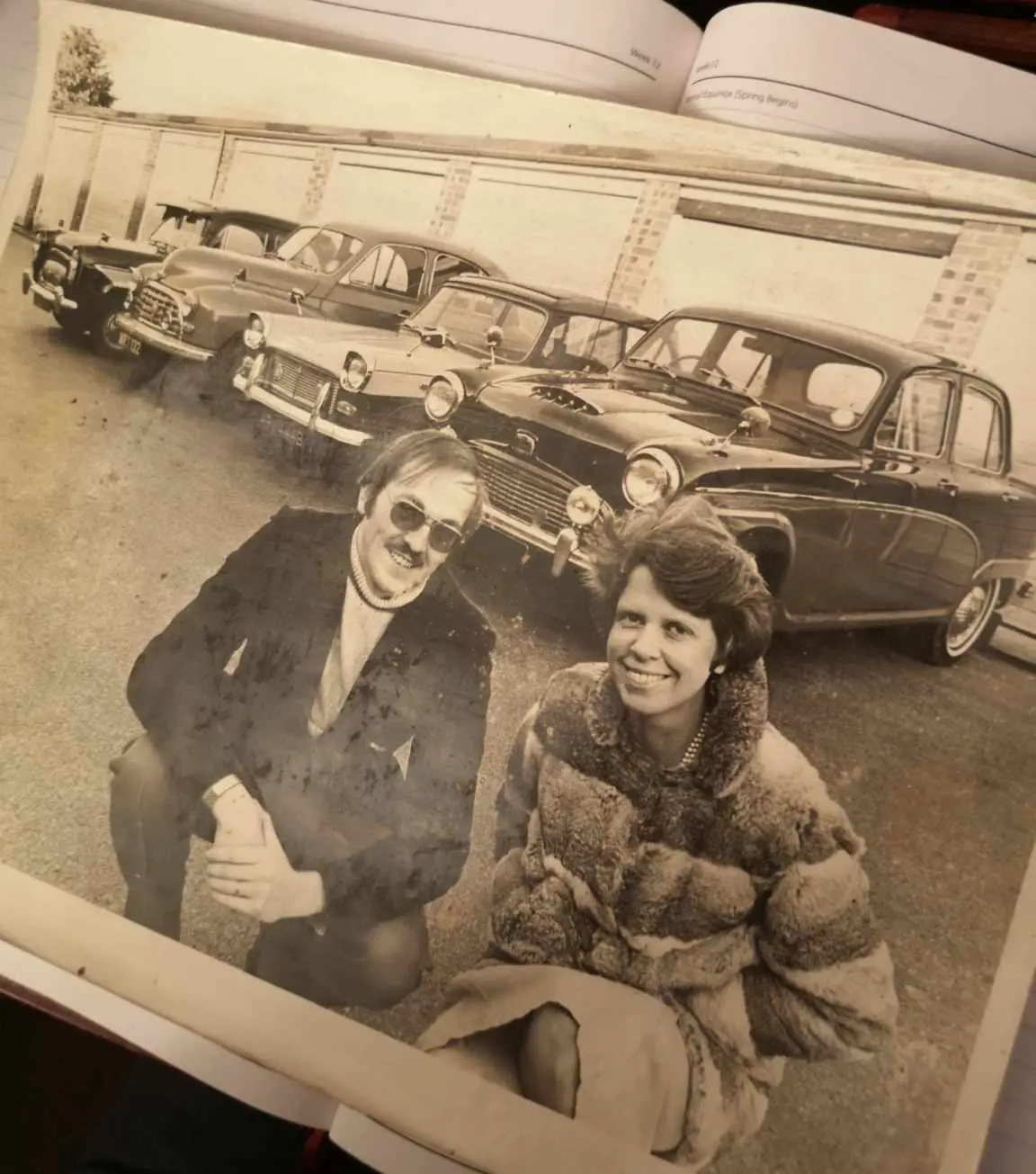

Triumph built its last Herald in 1971 after founding a dynasty of the Vitesse, the Spitfire, the GT6, and the Bond Equipe. It had also been made around the world and Indian production of the ‘Standard Gazel’ lasted until 1983. There did seem to be a period in the 1970s when flared-trousered Dolomite owners regarded the Herald as a relic of the past, along with winkle-picker shoes and Adam Faith records. But by the following decade, it was a cornerstone of the British classic car movement.

And as for the Herald’s appeal back in 1959, here are my impressions of a very early Saloon for Classics magazine. In my view, the typical owner would have been:

‘a cool cat (in his mind at least), one who delights in wearing an Italian-cut suit and who regularly dons a pair of sunglasses when visiting the local corner shop. For the up and coming estate agent known to say ‘Ciao!’ (in a Portsmouth accent) to the head waiter at the trattoria, there can only be one choice of a new car.’

Plus, they were allegedly very adept at out-running police Wolseleys -