Rules, O-Kei? A potted history of how the light automobile put Japan on wheels

07 February 2023

(Part 2: 1960-1968)

In Japan’s rapidly expanding, fraught and narrow cities, Kei cars were a boon. Their diminutive size wasn’t enough, however: legislation banning on-street parking had been adopted in Tokyo in 1957. A national Garage Act had arrived by 1962, and three years later, almost every major city required a garage certificate (shako shomeisho) as proof of off-site parking.

Not only were Kei cars cheap, as per MITI’s requirements, but they were exempt from the Garage Act in most built-up areas. As the Parking Reform Atlas notes, however, Kei cars would still be towed away if they were left on the street overnight.

The Japanese working their way up didn’t need any further persuasion to purchase Kei cars in their droves: compliant cars from almost every manufacturer followed the Subaru 360’s lead. With a verbose template, makers were free to diversify, within limits.

It was becoming apparent that Kei models could offer everything a larger car could, albeit scaled down – a point not lost on Mazda, whose four-stroke R360, released in May 1960, undercut Subaru’s 360 while outperforming it on the open road. Demand for Japan’s cheapest four-wheeled car was ferocious: 4,500 units were shifted on its first day of sale, a feat which inducted it into the Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan’s Hall of Fame.

At 300,000 yen (approximately £1,700 in today’s money), it made the Fuji Cabin 5A (at 230,000 yen or £1,300) look like the enclosed scooter it still closely resembled. Crucially, it could also be purchased with a two-speed torque convertor, which removed the need for a clutch pedal – a more than welcome benefit in the nascent traffic building in Japanese cities.

It was the first time the fluid torque converter, developed by latter-day furniture manufacturer Okamura, had been used in mass production; its range of Mikasa Touring cars, so equipped, had been discontinued that same year owing to poor sales.

They were too large and expensive to qualify as Kei cars – but the Touring’s torque convertor unit, employed in another ex-aircraft manufacturer’s Keitora, the Cony Guppy, introduced thousands of youngsters to the joys of driving.

The Guppy lasted a year; after fewer than 5,000 were built, it was discontinued in 1961. Maker, Aichi Kokuki, was eventually absorbed into Nissan (Datsun) as a powertrain maker four years later, though it carried on making the Guppy’s successor, the 360, for another decade.

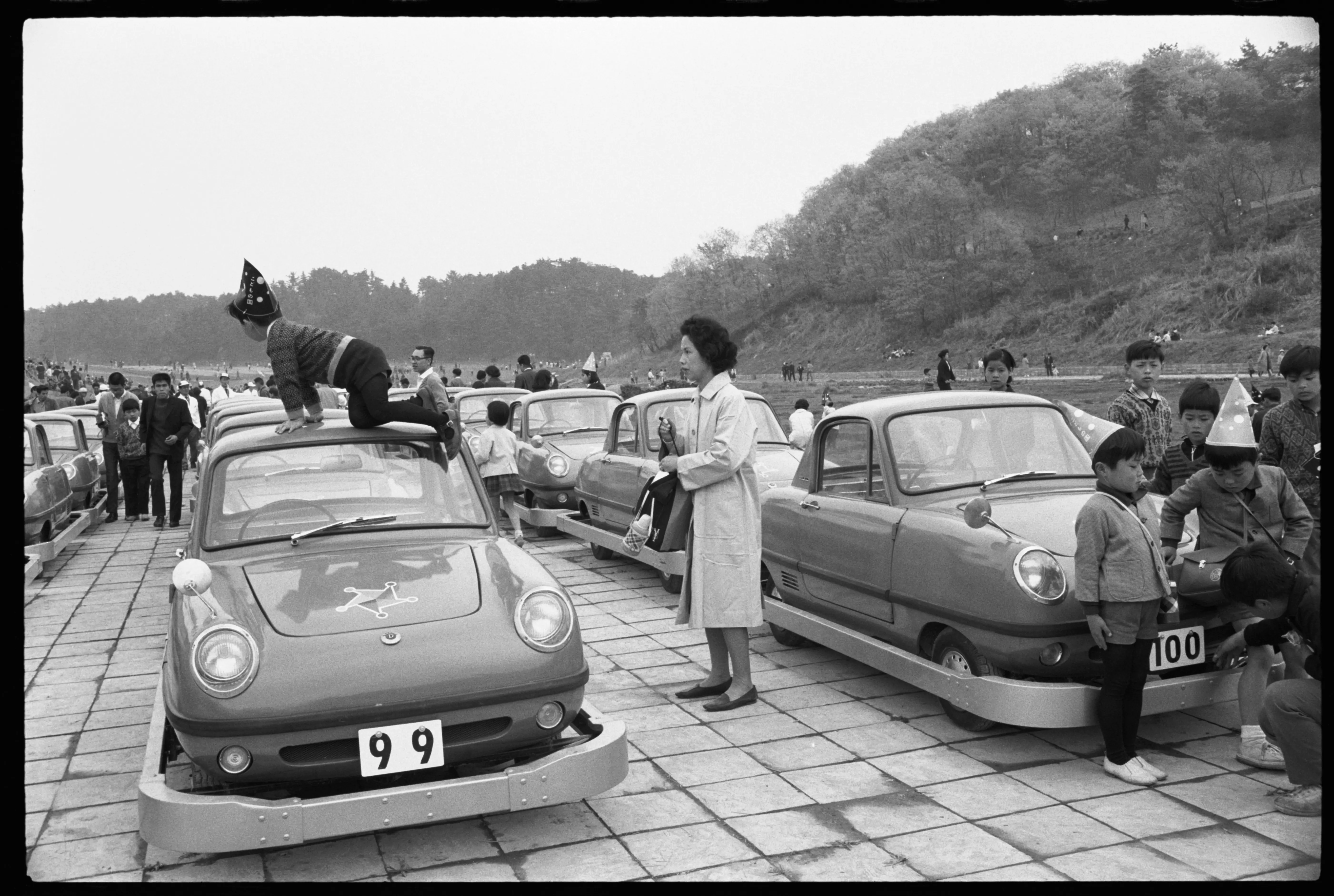

Using the earlier car as a basis, it built a fairground attraction in the Datsun Baby; 100 examples of this Guppy based doorless coupe were made for children to drive at the Kodomo no Kuni Children's Park in Central Japan. Slowly but surely, the Kei car was etching itself into Japan’s automotive consciousness.

Honda, known primarily for its motorcycles, was gradually edging towards car production, though its most important prototype of 1961, the S360, would act as a precursor to the bespoke Kei sports cars built during Japan’s febrile bubble economy of the early ‘nineties.

It ultimately decided to go with the larger-engined S500 of 1963 for production (and potential export), consigning the Kei-compliant S360 to the history books. Its engine and chassis lived on as a Kei pick-up truck, however, as the T360 entered the increasingly crowded commercial vehicle market the same year.

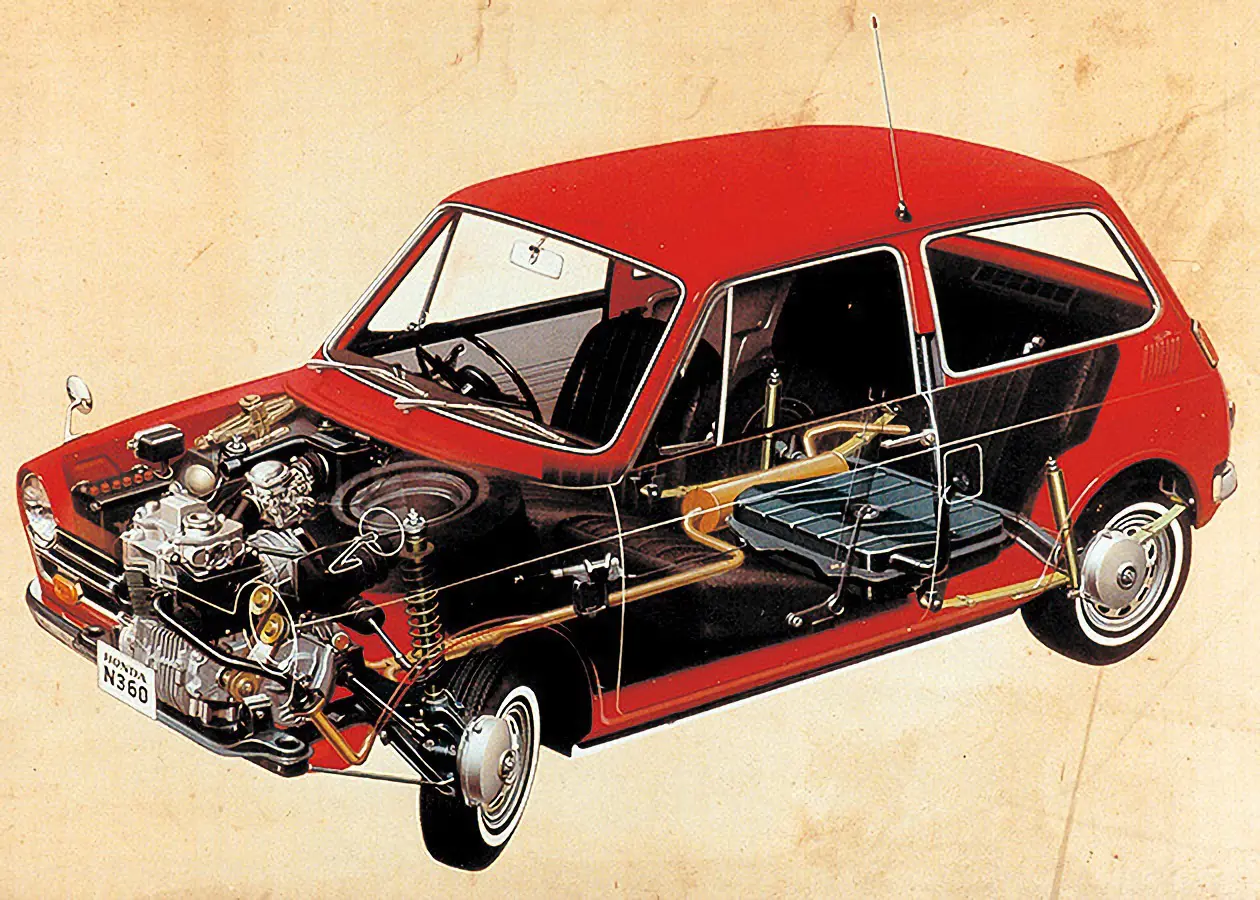

It was with the N360 of 1966, however, that Honda’s intent became clear. It was a domestic sales sensation, upping the power stakes to a heady 28bhp from its 354cc engine. Front-wheel-drive, a roomy-by-Kei-standards cabin and a top speed over 70mph put it at the top of the class.

The N360 did less well against the Mini 850 when it was imported to the UK a year later, and a larger engined ‘export’ N600 similarly failed to set our home (and North American) markets alight. That said, the three-speed Hondamatic automatic transmission, offered in the N360 and N600 AT, brought shift-free driving to the Kei car market for the first time, moving beyond the Okamura torque converter.

The N360 became such a staple of domestic life that it even appeared in a camera advert as a long distance steed, overtaking the likes of the Mazda Cosmo, Toyota 2000GT and the Datsun 240Z with a Pentax Spotmatic SLR dangling from the rear view mirror.

It was becoming abundantly clear, however, that Kei cars were Japanese cars for the Japanese alone, despite their mechanical durability. Sir Stirling Moss and Isle of Man TT winner Mitsuo Ito drove a Suzuki Fronte SS flat across the Italian Autostrada del Sole in 1968; there were no breakages.

Europe, meanwhile, ploughed its own small car furrow; Japan, with exports in mind, developed larger cars to meet demands at home and overseas. If you're looking for insurance for your import, Lancaster Insurance Services offer classic car insurance for Japanese import cars.

Kei cars made leaps and bounds in the ‘sixties, enough for many to use them as everyday cars. Suzuki concocted a publicity stunt in 1968 with the late Sir Stirling Moss to drive a Fronte SS through Italy to prove its durability (image: Suzuki).

The Cony Guppy donated its running gear and torque convertor to 100 low speed Kei cars built for children – by Datsun (image: Datsun).

Honda’s N360 set new Kei car standards, a ‘supermini’ in miniature, five years before the Fiat 127 (image: Honda).